The importance of a school’s curriculum is now at the forefront of education reform following Ofsted’s Chief Inspector, Amanda Spielman, highlighting the outcomes from recent research into curriculum in schools. She argues that, “accumulated wealth of human knowledge, and what we choose to pass on to the next generation through teaching in our schools (the curriculum), must be at the heart of education”.

The research into curriculum provision indicated unique curriculum designs, with the schools involved falling under one of three categories: knowledge-led, knowledge-engaged, and a skills-led approach.

In the knowledge-led curriculums, the report highlights the following evidence, “The leaders saw the curriculum as the mastery of a body of subject-specific knowledge defined by the school. Skills were generally considered to be the outcome of the curriculum, not its purpose.”

In the knowledge-engaged approach the report indicated the following, “These schools were less reliant on curriculum theory than knowledge-led schools. However, knowledge was not absent; it remained a focus, albeit to varying degrees. For these leaders, the curriculum was about how they could ensure that pupils can achieve both knowledge and skills.”

Finally, in the third approach, the skills-led curriculum, the research demonstrated, “In these schools, the curriculum was designed around skills, learning behaviours and ‘general knowledge’. Leaders placed an emphasis on developing the skills pupils would need for future learning, often referring to resilience, a growth mind-set and perseverance.”

Across all 3 curriculum approaches, the report indicated there were strengths and weaknesses in the different designs but that in both the knowledge-led and knowledge-engaged approaches the importance of the subject and its associated key vocabulary were stressed to students. This points towards the importance of seeing knowledge and skills as intrinsically linked, i.e. you demonstrate your knowledge through the skills you have mastered.

For curriculum design to be effective it should have the following aims:

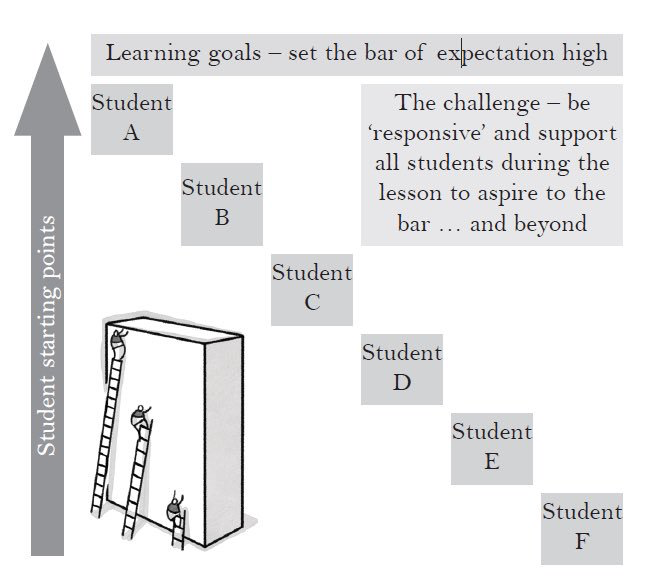

1) Provide students with a rich breadth of knowledge that enables them to deepen their understanding of the subject;

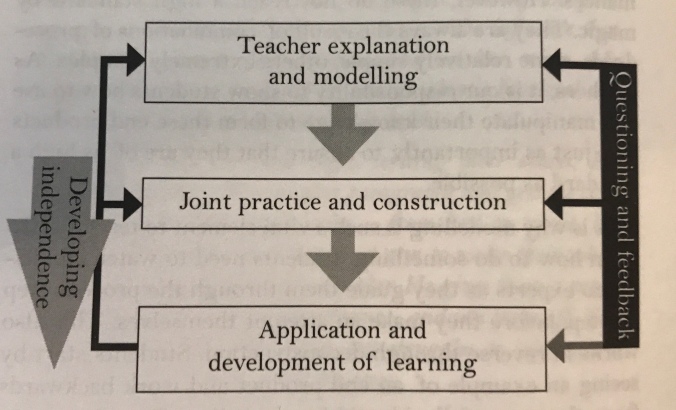

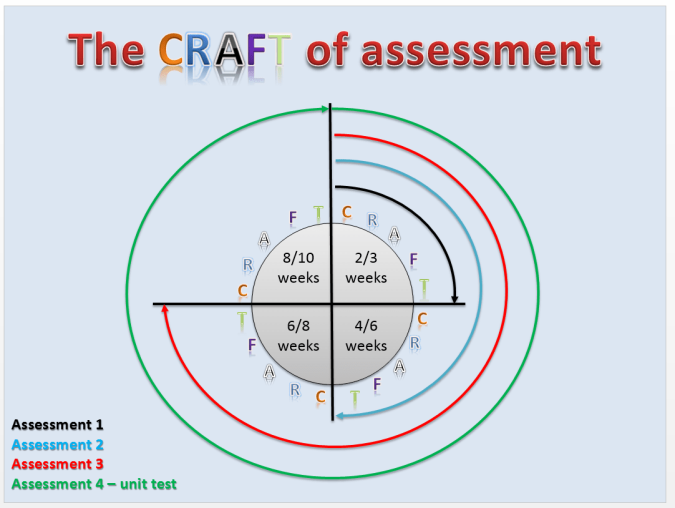

2) Create a curriculum that interleaves between overarching concepts and processes that underpin the subject allowing for deliberate retrieval and spaced practice;

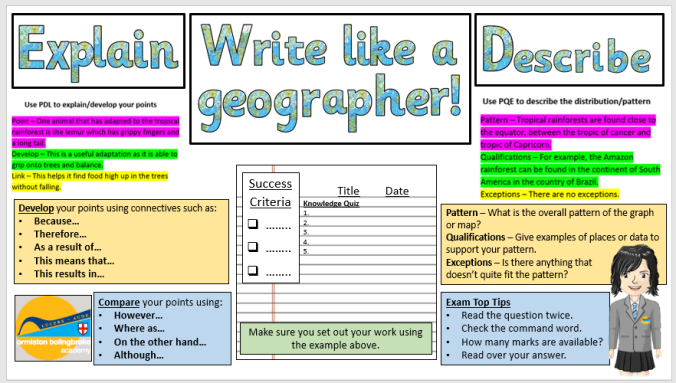

3) Make students explicitly aware of the inter-weaving skills that will enable them to demonstrate knowledge.

In considering our curriculum last year, this led to the creation of a 7 year curriculum plan with the main vision being to remove the three buckets of the Key Stages and look at our curriculum holistically. There are 7 key themes that underpin the curriculum: explanation writing, discursive writing, players, synoptic moments, geographical skills, statistical skills, and geographical enquiry. There has been an emphasis on promoting the importance of these skills, not just in geography, but also as part of the students wider curriculum through cross-curricular links with other subjects like English, Maths and Science.

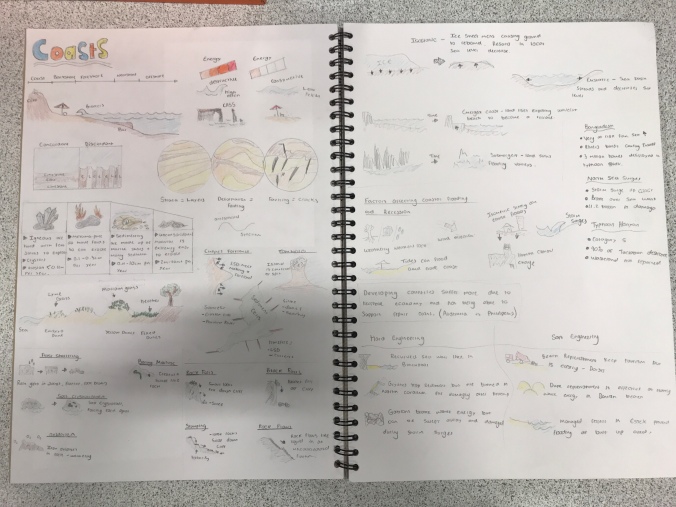

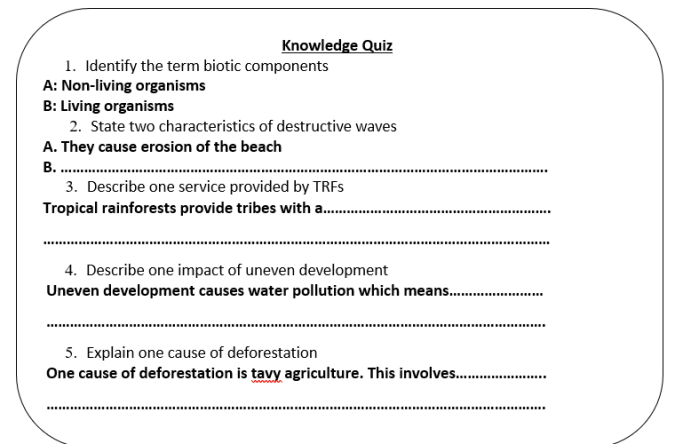

In doing this, our department time has been focused on an element of geography, for example coastal landscapes, and looking at how we could provide a rich breadth of knowledge that deepens student understanding as they move through the school years. Below is the beginning of this webbed approach to a SOW that covers how we intend to explicitly link knowledge and skills for coastal landscapes across the 7 years. The overarching key processes that students need to understand is erosion, weathering and mass movement. These are at the top and linked to the other aspects of coasts that require understanding of these processes, enabling teachers to focus on pedagogy, so that students deliberately practice these processes until they are embedded.